I am living a Tuberculosis nightmare. I get agitated when I think about it. I wish I had a sedative to calm my nerves as I write this.

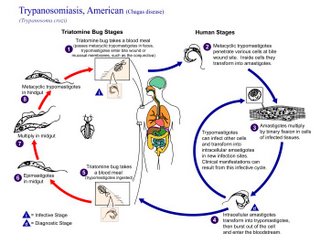

I am living a Tuberculosis nightmare. I get agitated when I think about it. I wish I had a sedative to calm my nerves as I write this.The background: HIV and TB are a deadly combination. Unfortunately, they are also both common diseases. One-third (1/3) of the world´s population has been exposed to tuberculosis and is walking around with latent disease.

Most HIV-negative people do not get sick with active TB after they have been exposed. A healthy immune system usually controls the TB mycobacterium. Nevertheless, a few scattered mycobacteria hide away, alive and well, even in the healthiest of hosts. This is called latent disease. Should the host become immunosuppresed, the hidden mycobacteria are more likely to "reactivate"--multiply out of control and blossom into an active TB infection.

HIV positive people who have been exposed to TB are 100 times more likely to get sick with active disease than non-HIV patients. Not only does HIV make TB worse, but TB makes HIV worse. HIV patients with active TB have higher HIV viral loads, and their CD4 counts fall faster than patients without TB. Many patients with HIV and TB coinfection die. In fact, tuberculosis is the leading cause of death in HIV positive patients worldwide-- most certainly in places like Puerto Barrios Guatemala.

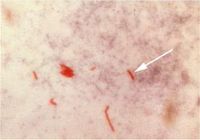

Doctors can usually diagnose TB in HIV-negative patients by ordering a sputum smear (pic at right). (1) Cough up glob of phlegm. (2) Smear phlegm onto microscope slide. (3) Throw on a few drops of dye. (4) look at slide under microscope. If pink "acid fast bacilli" are visible, the patient is deemed "AFB positive," and treated for active tuberculosis.

Unfortunately, smears are not a good way to diagnose TB in HIV positive patients. About 50% of HIV patients with active TB are "smear negative," which means that no organisms are seen under the microscope, even when the patient is swarming with them. The best way to diagnose TB in smear negative HIV patients is to send phlegm or other body fluid-- blood, cerebral spinal fluid, or urine-- for culture. Or, if you want to spend even more money, you can send the sample for a fancy DNA amplification test called PCR. Unfortunately, many "resource-constrained" (aka poor) places cannot afford to do TB cultures, much less PCR.

Public health authoçrities like the World Health Organization and the CDC have woken-up to the TB/HIV coinfection emergency. They also seem to have realized that poor countries cannot always send cultures, and therefore have trouble diagnosing smear negative patients. WHO recently published guidelines for diagnosing and treating smear-negative coinfected patients in resource constrained settings. These guidelines urge doctors to treat smear negative patients even in the absence of a confirmatory culture. When HIV positive patients have signs and symptoms of TB ("high- suspicion" patients), the guidelines recommend treatment, even if smears are negative and no cultures are available.

Unfortunately, the Guatemalan Ministry of Tuberculosis has not read the WHO guidelines. Or maybe they think Guatemalan coinfected patients are different from coinfected patients in other countries around the globe. Who knows what they are thinking? All I know is that many of our smear-negative patients cannot get treatment.

You can walk into almost any pharmacy in Guatemala and buy antibiotics, sedatives, narcotics, proton pump inhibitors, mega-dose injectable vitamin B12, and kill-your-kidney injectable NSAIDS without a prescription. But you cannot buy INH, Rifampin, or Ethambutol, the drugs used to treat TB. these drugs are only available from the Centros de Salud (primary health care centers). Unfortunately, when we send our smear-negative patients to the Centros de Salud for treatment, they are often told that they cannot get treatment unless they have a positive smear or culture. Our letters and phone calls are not much help.

What happens to our patients? An example: A 42 year old man with HIV, previously doing well on antiretroviral therapy came to the clinic with cough for a couple of weeks. We gave him antibiotics, an "empiric" treatment for bacterial pneumonia, and sent three sputum smears for AFB. All the smears came back negative. He was no better in a couple of weeks. He was losing weight and he looked weak and tired. We sent him for a chest X-ray (shown above right). It does not take a pulmonologist or radiologist to see that the left side is different than the right side. Hummm.... HIV positive, cough, weight loss, night sweats, not better with antibiotics.... could it be... TB??? But when we sent the patient to the health center with a letter and a copy of his X-ray, he was told he could not get TB treatment because his smear was negative. The health center employee would need to write a letter to the central office in Guatemala. If they approve empiric treatment in one of their upcoming meetings, the patient might be approved for empiric treatment. In the meantime, he would have to wait. It could take weeks, even months for the central office to get to his case. I blew my stack when he came back and told me the story. My temper tantrums do not help.

Until Guatemala changes it´s practice for management of smear negative TB in HIV positive patients, our patients are in serious trouble. In fact, we are all in serious trouble. I can only hold my breath for so long, before I breathe in one too many AFBs.

I'd like to tell you about these cases

I'd like to tell you about these cases , but first I need to give you some back-ground about the project and the hospital, and unfortunately that makes my head ache. Perhaps I will be able to do this one day when I'm not dying of heat stroke.

, but first I need to give you some back-ground about the project and the hospital, and unfortunately that makes my head ache. Perhaps I will be able to do this one day when I'm not dying of heat stroke.